Before ‘China-Bashing,’ there was ‘Japan-Bashing.’ In the early 1980s, Japan’s economic rise spurred fear and criticism from elected officials and everyday Americans alike. Federal lawmakers destroyed Toshiba products in the aftermath of a company scandal. Many contemporary movies, such as Blade Runner and Back to the Future Part II, projected the American fear of Japanese businesses and culture infiltrating the US; Japanese goods comprised 21% of US goods imported in 1986–more than China’s share of US imports today. However, by the middle of the 1990s, ‘Japan-Bashing’ and Japan’s exceptional growth ceased to exist.

In the 1990s, Japan underwent a spectacular financial crisis from which the country still has not fully recovered. But along the way, the country experienced one of the most incredible bubbles in human history. Japan’s boom-to-bust tale provides many universal insights on critical economic phenomena, covering the drivers of bubbles, the costs of crashes, and the lasting effects of poor financial supervision.

By the 1950s, Japan had recovered from the Second World War with a strong economy. Exports grew, and Japan upgraded from textiles and cheap goods to machinery and electronics. The country registered a massive trade surplus, enriching its citizens. In 1968, Japan became the world’s second-largest economy.

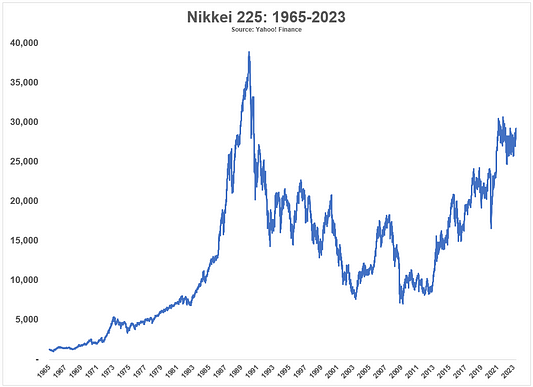

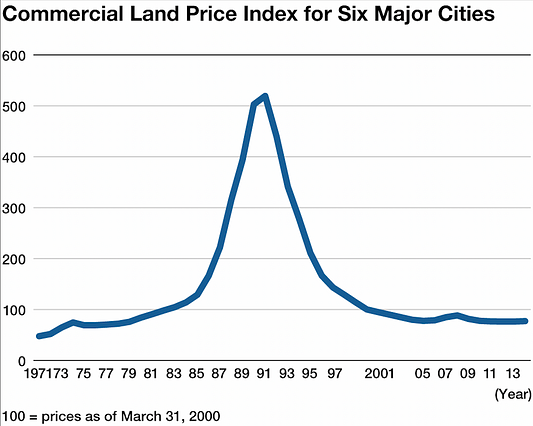

Even before the bubble, investment was driven by real estate returns. Because of banking regulations, the real rate of interest was negative. However, property owners could receive strong real returns. From 1955 to the mid-1970s, the housing market increased forty-fold. The stock market was just as impressive, rising from 100 in 1949 to 6,500 by the early 1980s.

At this point, Japan’s economy showed no signs of a bubble; however, financial deregulation and a growing money supply soon helped create the conditions for the ensuing real estate and stock bubble. At the beginning of the 1980s, the US government began pressuring the Japanese government to liberalize its financial sector. Already disconcerted by Japan’s growth, US officials felt it was unfair that Japanese firms could expand into the US while US firms faced burdensome regulations. In response to US pressure, Japanese regulators increased the ceiling on interest rates, making banking much more profitable.

The US government also wanted to liberalize Japanese firms so that they could purchase US Treasuries, thereby funding the growing US deficit. Japanese firms were highly limited in the possibilities of foreign investments; however, Japanese regulators soon loosened restrictions on investment opportunities, including in real estate.

Currency intervention increased the Japanese money supply. As the Japanese economy grew and outperformed competitors, the Yen appreciated, harming export-oriented firms. While an artificially weak Yen improved exports, more money flowed into the country. All of these forces helped provide fuel for the ensuing bubble. Financial deregulation and increased money supply made credit more abundant, which caused financial markets to flourish.

The real estate market and banking sector combined to form the bubble. Real estate and stock price increases led to growth in banks’ capital, which catalyzed growth in loan books. Due to financial deregulation, banks began loaning to property owners at rapid rates. Loan losses were slim due to the rising real estate market. Furthermore, as property prices and stock values rose, banks lent more, and individuals invested in more property and stocks, causing financial markets to sprout. The financial system generated a positive feedback loop whereby rising real estate and stock prices increased bank capital, which raised real estate and stock prices, and so on.

The credit loop was not just endogenously generated. International investors significantly contributed to its expansion. Investors worldwide purchased Japanese securities as the country’s markets and currency sprouted. From 1985 to 1987, the Japanese Yen appreciated by 50 percent. Investors benefited from both increasing prices and the rising Yen. The Yen began to strengthen as capital flowed into the country, incentivizing even more investors to invest in Japanese securities.

In the 1980s, real estate increased by over 500%. The market grew to twice the value of the US market, even though Japan is five percent of the area of the US. By 1989, stock prices reached 40,000 after starting the decade at 6,500. Share volume more than doubled. The system entered into a bubble.

In a bubble, irregular economic behavior emerges due to new financial opportunities–Japan was no different. Industrial companies began primarily investing in real estate. Since the rates of returns on steel and automobile production were less than property returns, many nonfinancial corporations began contributing a significant amount of internal and borrowed capital to Property, Plant, & Equipment.

Real estate returns and mortgage rates eventually outpaced rental returns, meaning rental incomes could no longer cover mortgage payments. Nevertheless, there was no need to fear. As long as real estate values increased, property owners could borrow more, taking out new mortgages to pay off their first. The credit supply was so abundant that interest payments were funded with new loans–assuming property prices increased.

The spending habits of Japan’s rising billionaires and corporations were stunning. Over 10,000 items of French art were purchased and brought to Japan during the bubble–with most leaving after the crash. The highlight was the $90 million purchase of Van Gogh’s The Portrait of Dr. Gachet. Developers constructed hundreds of golf courses and shopping centers for the new upper class.

Many burgeoning firms competed to see who could purchase the most expensive and impressive office. Mitsubishi Estate acquired the Rockefeller Group, inheriting the renowned Rockefeller Building in New York. Mitsui Real Estate Company purchased the Exxon building in New York for $610 million, ignoring that the asking price was significantly lower. Many of these purchases were only possible due to the overflow of Japanese credit.

As the bubble progressed, lender expectations improved, leading to excessively loose credit standards. New 100-year, three-generation mortgages popped up. Grandkids would be paying off their parent’s parent’s mortgage. Reduced lending standards also reduced the difficulty of fraud. The Yakuza began infiltrating many banks, pressuring lenders to provide them with favorable loan terms; however, rising real estate prices hid these risky practices.

The most absurd feat of fraud was only discovered after the bubble–as most fraud is–when a bank discovered one shop owner had received the Yen equivalent of billions of dollars from her banker friend. Once the market crash revealed the fraud, the incidents would compound Japanese banks’ losses.

Central bank tightening catalyzed the crash. The governor of the central bank grew concerned that expensive housing prices would disintegrate the country’s social harmony. Starting in 1989, the Bank of Japan increased interest rates and instructed banks to reduce their exposure to real estate. By the start of 1990, the property and stock market collapsed from the reduction in credit.

Bubbles and crashes both operate under positive feedback loops. Where an expansion in credit increases asset values, a fall in credit causes prices to crash. As asset prices fell, loans became underwater, meaning the mortgage exceeded the property price. Banks then began repossessing real estate at distressed prices. Meanwhile, the credit reduction caused property owners to default on their mortgages. As previously mentioned, many owners completed interest payments with new loans; with the fall in credit, however, debtors could no longer find new loans for interest payments and defaulted in droves.

International investors also began fleeing the country. Investors sold both securities and the Yen, causing the stock market and Yen to fall. Just as a rising Yen incentivized further investors to purchase Japanese securities, a weakening Yen caused more investors to sell out of their Japanese holdings. The floating exchange rate mechanism both compounded the rise of the bubble and exacerbated the fire sale.

Banks began accumulating significant–undesired–real estate holdings as their debtors defaulted and went under. They did not just receive houses, however, but all the excessive investments from the bubble’s peak. French paintings, golf courses, and skyscrapers were repossessed and added to banks’ assets at distressed prices. Loan losses surged.

The central bank did not significantly intervene in the financial system until 1997, when four major firms became insolvent. By then, however, asset values had crashed, and the banking system was undercapitalized and flooded with bad debt. The central bank began protecting solvent and even insolvent institutions. By protecting insolvent institutions, the central bank created zombie banks, which the Bank of Japan was too concerned to let fail. These banks contained no operational capabilities and contributed no economic growth; however, they cost the government over 20% of GDP to protect. The economy soon fell into a significant and long recession, contracting 1.3% and 1.5% in 1998 and 1999, respectively. Nowadays, the 1990s are now remembered as the Lost Decade.

Japan also struggled with deflation for 15 years after the crisis. Deflation is an exceptionally difficult economic problem. Since purchasing power increases as prices fall, individuals are incentivized to reduce consumption. Deflation also dissuades nonfinancial investment as falling prices reduce future returns on investments. The real price of debt also increases in deflationary environments, making debt servicing more difficult. As deflation then warrants even more deflation, economic growth can nearly freeze.

The government required eye-watering expenditures to alleviate the economy. Public debt stood at 236% of GDP by 2019. Nevertheless, Japan still has an upward path before the country returns to a dynamic source of growth.

The Japanese bubble and crisis exhibit many significant economic phenomena and lessons. The country details the critical role of credit in facilitating the bubble and the crash. Also revealed is the volatile role international investors can play in a floating exchange rate regime. Lastly, the government resolution showed the lasting effects of inadequately addressing financial instability. At the start of the 1990s, Japan could not own enough French paintings, but by the end of the decade, the country was fighting insolvency and deflation.