Earlier in the year the Swiss National Bank, Switzerland’s central bank, released its latest report. While reading the news covering the bank’s financial results, I was surprised twice.

First, it turned out that Switzerland’s central bank still has its stock trading on the SIX Swiss stock exchange. Now that’s what I call Die-Hard Capitalism!

Second, I was surprised by the reaction of many observers to the financial results reported by the SNB. They were virtually shocked that it reported the largest loss – 132 Swiss francs (143 billion US dollars) – in its 115-year history (see Reference 1 below). Switzerland has accumulated foreign exchange reserves to the tune of more than 1 trillion US dollars invested in foreign currencies, gold, stocks, and, of course, various government bonds. Therefore, the fact that the bank reported stock- and foreign exchange-related losses does not surprise anyone. However, people are often shocked when faced with large losses resulting from investments in “safe” government bonds.

Just ask any pension fund or insurance company in any developed country whether government bonds deserved their “safe-haven” status in 2022 in the context of the most serious geopolitical crisis in the last 30 years, dramatic supply chain disruptions, and the highest inflation rates in the last 40-50 years.

The government bond topic is rapidly becoming politically sensitive when you see newspaper headlines such as these: “A million older workers face new pensions misery: Bond rout wipes a third off funds – just as retirement looms. The retirement plans of up to a million workers lie in tatters as the recent collapse in supposedly safe government bonds battered the value of their pension pots.” (see Reference 2 below).

Despite the fact that the bond market is larger than the stock market, the vast majority of non-professionals and many professionals (!) have only a very vague understanding of bonds and interest rates. Therefore, it would be reasonable to recall the basics of financial theory and history.

The theory of finance says that the purchase of bonds provides their owner with the opportunity to become the creditor of a company, an international institution, or a government. In other words, bonds are loans traded in the financial markets.

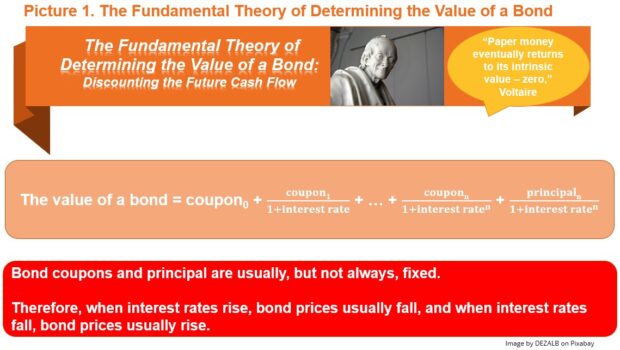

The fundamental theory of finance also says that the cost of any financial instrument depends on the amount of cash flow you can expect to receive from investing in it. What is the cash flow an investor can expect to receive when he or she purchases a bond? We have already mentioned that bonds are, in fact, market-traded loans issued to governments or companies. That is why, when purchasing a bond, an investor can expect to receive usually fixed periodic payments (bond coupons), as well as the principal or face amount of this bond when it is redeemed.

Still, the simple addition of a sequence of cash flows from different time periods is not appropriate since “Paper money eventually returns to its intrinsic value – zero,” as the famous French philosopher Voltaire put it. That is why the fundamental theory of finance also asserts that the cash flows received in the future have less real purchasing power compared to the cash flows received today. Scientifically speaking, the value of a financial investment depends on the discounted cash flow that the investor can expect to receive when making this investment (see picture 1 below).

Discounting, or value reduction, occurs by using interest rates. Interest rates consist of three components: first, a risk-free interest rate that reflects the time effect between consumption today and consumption in the future. It is usually paid by the governments of the most reliable borrowing countries; second, a market-risk premium paid by all private companies since they carry a higher risk of not meeting their obligations when compared to governments; third, a specific-risk premium paid by each specific company.

Since both the amount of bond coupon payments and its principal amount, when the bond is redeemed, are usually fixed, it can be concluded that changes in its price are almost entirely explained by changes in the interest rate used to discount the bond’s expected cash flows. However, these changes may occur for various reasons. The changes may occur because there is an increase in the risk-free interest rate delivered by the central bank fighting high inflation. There might also be a rise in the market-risk premium due to some economic or political upheavals, for example. Or there might be a rise in the specific-risk premium for a particular company due to any negative events directly related to it. Still, the general conclusion is straightforward: when interest rates rise, bond prices usually fall, and when interest rates fall, bond prices usually rise.

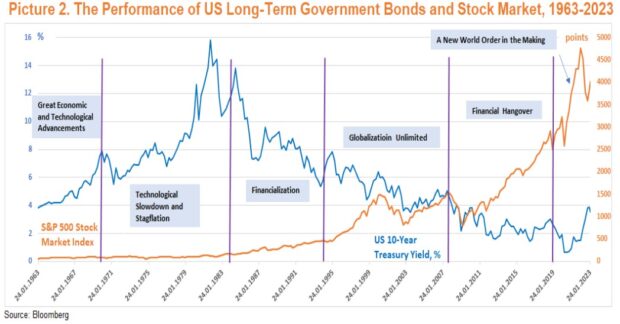

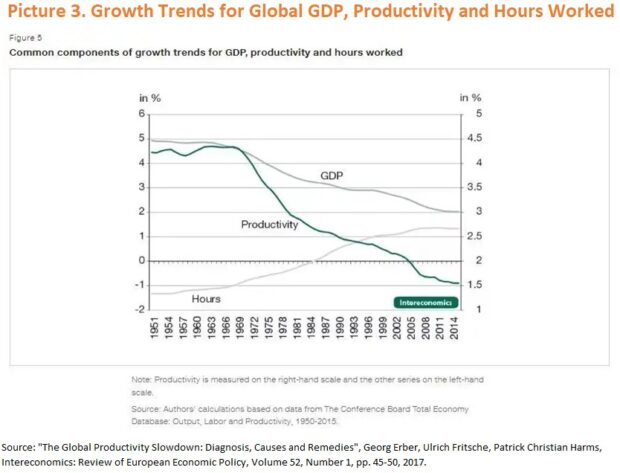

Economic history strongly suggests that that the most important variable in the world of finance is the PRICE OF LONG-TERM MONEY, that is long-term interest rates. It also says that the most important variable in the world of real economy is LABOR PRODUCTIVITY. Did you know that the growth rate of real wages is determined by the growth rate of labor productivity? Now you can see why the growth rate of real wages has been so slow for decades (see Picture 2 and Picture 3 below).

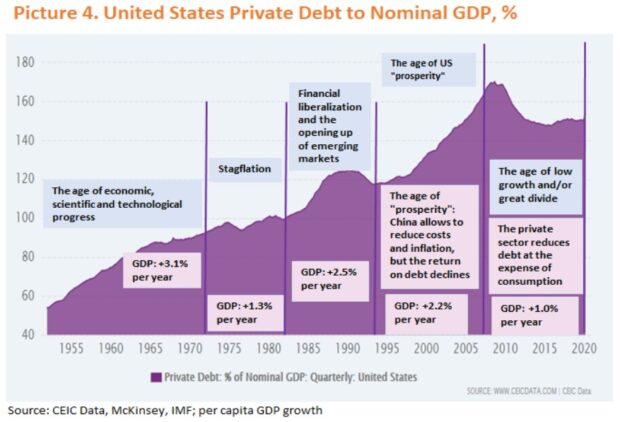

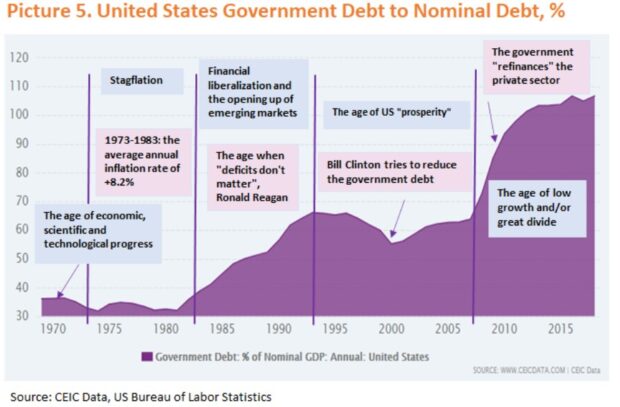

If we are not sufficiently productive, then various types of financial engineering — both monetary and fiscal — will only help us buy some time before we are forced to curb our consumption (see Picture 4 and Picture 5 below).

Now we can present the shortest possible course of economic and financial history of the last 60 years:

Stage 1. From the late 1960s to the early 1980s. Technological Slowdown and Stagflation. The growth rate of technological progress and labor productivity started slowing down. This led to a slowdown in the growth rate of real GDP. A loose monetary and fiscal policy aimed at supporting the faltering economy fueled demand-pull inflation. The gold standard was abolished. Now fiat (“paper”) money was no longer pegged to gold. This spurred inflation even further. Negative supply shocks (two oil crises) paved the way for shortages and cost-push inflation (“stagflation”). Inflation was soaring, long-term interest rates were soaring, stock prices were languishing.

Stage 2. From the early 1980s to the early 1990s. Financialization. The US central bank started implementing a shock therapy strategy by hiking interest rates sharply, thereby slowing down inflation, and inevitably causing a deep recession in the economy. To support the economy and consumption a loose fiscal policy was initiated. Most importantly, the financial sector was liberalized to make it easier for companies and private individuals to borrow money. The growth rate of real GDP started to accelerate. Long-term interest rates were falling sharply, while stock prices were rising. The growth rate of labor productivity was still slowing down.

Stage 3. From the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s. Globalization Unlimited. A positive supply shock following the opening-up of China, the former Soviet bloc, and other emerging markets. New supply chains, the outsourcing of manufacturing facilities to poorer countries, and the global migration of labor reduced costs and eliminated the threat of cost-push inflation. This allowed to lower interest rates even further, thus encouraging private individuals to borrow more to support consumption. Finally, demand-pull inflation started to reappear. Stock and other asset prices were rallying due to rising profits, since the demand-pull inflation for final products was far above the cost of resources, labor, and borrowed money. The growth rate of labor productivity was still slowing down.

Stage 4. From the late 2000s to the late 2010s. Financial Hangover. The declining marginal economic effect from additional private debt reached its tipping point: more private debt could not support more consumption and higher asset prices anymore. Asset prices started to collapse, thus undermining the creditworthiness of private borrowers and their lenders. The governments started to refinance the private sector through stimulus programs, while the central banks started to refinance the governments by buying public debt and lowering long-term interest rates to zero and below. The private sector stabilized its debt situation but at the expense of lower consumption. Inflation was subdued. The growth rate of real GDP was meagre. Stock prices recovered and resumed their meteoric rise since, first, input prices (resources, labor, and interest rates) were falling; second, the amount of available liquidity was substantially exceeding that of investable opportunities. Cryptos, fintech and other alternative assets were thriving for the same reason. The growth rate of labor productivity was becoming negative in some countries.

Stage 5. From the late 2010s to now. A New World Order in the Making. A protracted period of low economic growth was undermining political stability around the world. Geopolitical and domestic tensions were visibly on the rise. Cracks began to appear in global supply chains due to trade wars, the pandemic, and military conflicts. This led to the resurgence of cost-push inflation (“stagflation revisited”). The central banks started raising interest rates, while asset and stock prices are falling significantly. It is quite probable that the growth rate of labor productivity has become negative in most countries.

Now you probably understand that the era of financialization required low interest rates. Furthermore, the era of financial hangover required even lower rates. As a result, long-term interest rates were steadily declining leading to a legendary Great Bond Bull Run of the last 40 years.

However, there is no such thing as miracles, particularly, in finance. That is why these developments also meant that the likelihood of a sharp rise in inflation and interest rates at some point in the future was extremely high too. The two remaining uncertainties were the timing and magnitude of this almost inevitable rise. As we now know from economic theory, a rise in interest rates implies a fall in bond prices. Furthermore, the longer the maturity of a bond is, the more it is exposed to a rise of long-term interest rates.

Thus, before investing in long-term government bonds, remember the following:

1. In terms of credit risk long-term government bonds are safe if they are issued in the national currency of an issuing country.

2. Since long-term government bonds may have maturities of 10, 30, 50 or even 100 years, in terms of interest rate risk, currency risk, liquidity risk, and inflation risk, they may be as risky as other assets (!).

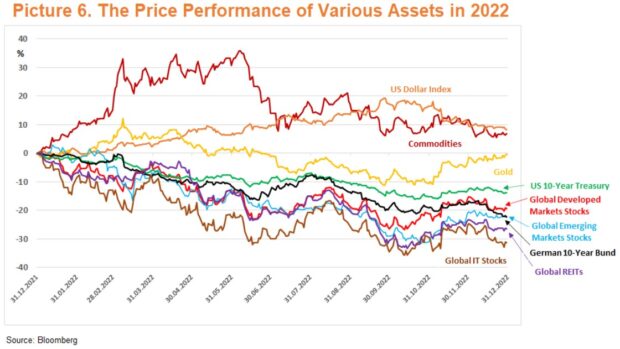

3. In terms of interest rate risk long-term government bonds are safe only if their periodic coupon payments are floating. This means that the floating coupons are periodically adjusted to reflect changes in short-term interest rates. In most cases, however, periodic coupon payments are fixed. Therefore, a rise in long-term interest rates has a negative impact on the price of such fixed-rate bonds. That is why in 2022 the prices of long-term government bonds issued by developed countries fell sharply in unison with stock prices (see Picture 6 below).

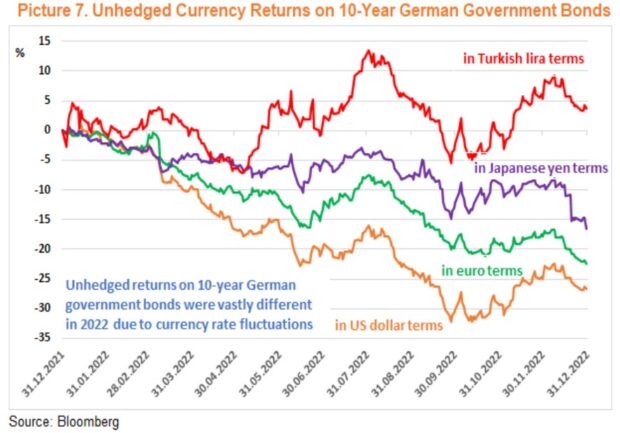

4. In terms of currency risk if you purchase a government bond denominated in a foreign currency for the issuing country, then its credit risk is higher than the credit risk of an identical bond denominated in the national currency of that country. Currency risk also arises if you purchase a government bond denominated in a currency other than your base currency. For example, US investors who held unhedged euro-denominated German government bonds during 2022 suffered losses not only resulting from a fall in bond prices, but also from a fall in the euro exchange rate versus the US dollar. At the same time, Turkish investors gained from a rise in the euro exchange rate against the Turkish lira (see Picture 7 below).

5. In terms of liquidity risk illiquid issues of government bonds may have a price disadvantage compared with identical liquid issues. For example, investors may demand an illiquidity premium for government bond issues that are small in terms of size. If you need to sell such a paper urgently, you may find out that its bid price is reduced by the amount of this illiquidity premium.

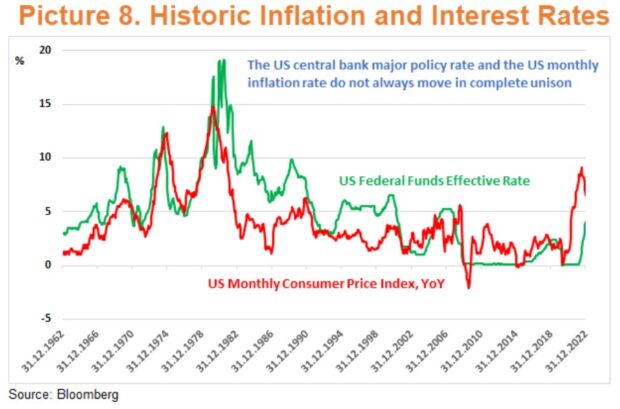

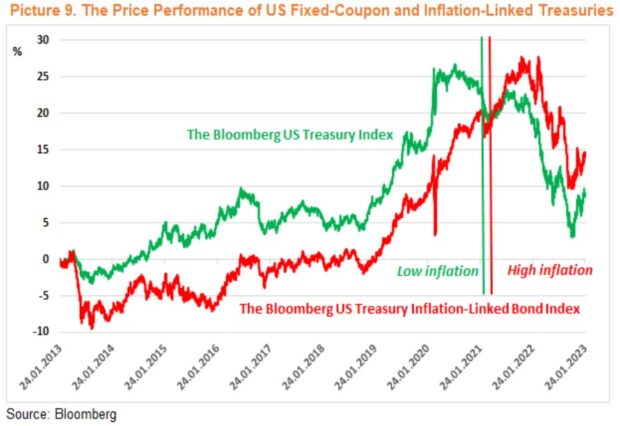

6. In terms of inflation risk even floating-rate government bonds do not guarantee that their prices will adjust to fully reflect changes in the rate of inflation (see Picture 8 below). For example, the monthly inflation rate in the United States in 2022 peaked at 9.1%, while the 6-month US dollar LIBOR did not exceed 5.25%. In the eurozone the monthly inflation rate peaked at 10.6% in 2022, while the 6-month EURIBOR interest rate did not exceed 2.8%. Investing in government inflation-linked bonds whose coupons are regularly adjusted to reflect changes in the rate of inflation may help you hedge against consumer price rises to a greater degree. Though in a low inflation environment they may demonstrate a significant price underperformance too (see Picture 9 below).

John Maynard Keynes, one of the most famous economists of the 20th century, as well as a successful investor and speculator, once said that “in the long run we are all dead.” To paraphrase him slightly, I would say that when investing in bonds remember that in the long run long-term government bonds are safe, but we are a long time dead.

References:

1. “SNB $143 Billion Record Loss Costs Swiss Usual Payout”, Bastian Benrath, Bloomberg, 9 January 2023.

2. “A Million Older Workers Face New Pensions Misery: Bond Rout Wipes a Third Off Funds – Just as Retirement Looms”, Patrick Tooher, This Is Money.co.uk, 31 December 2022.